MYTH 1: Evolution is just a theory, not a fact.

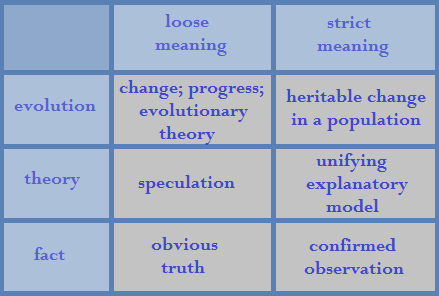

When I say I have a theory, it means that I have a guess, a conjecture. But when a scientist says she has a theory, it means that she has a working explanation for a large set of facts. When we confuse these two senses of ‘theory’, we can misunderstand the scientific standing of the ‘theory’ of evolution.

In science, a theory is one of the most sturdy and well-tested ideas, rather than one of the least. Strictly speaking, a scientific theory can never become a ‘fact’ no matter how well-supported it is, because a theory is an overarching explanation rather than a mere observation. Thus, the idea that matter is made of atoms is still the ‘atomic theory’, and the idea that microorganisms cause disease is still the ‘germ theory’.

Because theories make predictions about what will happen in the future, they can be tested and refined over time. Around the 1930s, Darwin’s original theory was replaced by the modern synthetic theory. This “neo-Darwinian” theory incorporated Gregor Mendel’s account of how offspring inherit traits. Mendelian genetics has helped produce the scientific definition of the actual observed process of evolution — as ‘change in a population’s inherited traits’. A common source of confusion is mixing up the physical process, ‘evolution’, with ‘the theory of evolution’ (with explains the process). The process — which can be seen every time children aren’t exact clones of their parents! — can be called a ‘fact’ in the strict sense, whereas the theory of evolution is only a ‘fact’ in the looser sense of being ‘something we know is true’.

So what does the theory actually tell us?

In biology, evolution is the change in a population’s inheritable traits from generation to generation. It boils down to 4 core ideas:

- Heredity. Parents pass on their traits to offspring.

- Variation. Offspring differ slightly from their parents, and from each other.

- Fitness. Some of these differences are more helpful for reproducing than others.

- Selection. Offspring with more helpful traits will in turn have more offspring, making the traits more common in the population.

Over time, this simple process of small incremental changes can have dramatic results. As traits become more common or rare in the population over millions of years, a species gradually changes, either randomly or by the environment’s selection of certain helpful traits, into a new species — or branches off into several. This process is called speciation.

MYTH 2: Evolution teaches that we should live by ‘survival of the fittest’.

‘Survival of the fit’ is a better characterization of Darwin’s theory of selection than ‘survival of the fittest’, a phrase coined by the social theorist Herbert Spencer. Selection simply states that whatever organisms ‘fit’ their environments will survive. When resources are limited, competition to survive certainly plays a role — but cooperation does too.

The idea of ‘survival of the fittest’ has been used to justify Social ‘Darwinism’, which amounts to a philosophy of ‘every man for himself’. However, a number of biological misunderstandings underlie the notion that pure selfishness helps the group or the individual. First, even if this were true in nature, that would not automatically make it a good thing — germs cause disease in nature, yet that doesn’t mean we should try to make ourselves sick. Do we want to emulate nature’s brutality, or mitigate it?

Second, the ‘fittest’ species are often the best cooperators — symbiotes, colonies of insects and bacteria, schools of fish, flocks of birds, herds and packs of mammals, and of course societies of humans. Moreover, most ‘weaknesses’ are not genetic, nor so severe that they make the individual unable to contribute to society.

‘Fitness’ also changes depending on the environment. There is no context-free measure of fitness, and what is ‘weak’ today may be ‘strong’ tomorrow. Mammals were ‘weak’ when dinosaurs dominated the planet, but strong afterwards. Which brings us to the next myth…

MYTH 3: Evolution is progress.

When we speak of something’s ‘evolving’, we usually mean that it is improving. But in biology, this is not the case. Most evolution is neutral — organisms simply change randomly, by mutation and other processes, without even changing in fitness. And although evolution can never be harmful in the short term, since a harmful trait by definition won’t be selected, the problem is that evolution only cares about the short term. Although in the long run small evolutionary improvements can add up to massive advantages, it’s also possible for short-sighted, immediate benefits to evolve which doom a species in the long run. This is especially common if the environment changes.

The illusion of progress is created because all the evolutionary ‘dead ends’ tend to end up, well, dead — dead as the dodo. But the idea that evolution has any long-term ‘goals’ in mind derives from us not noticing two things. First, we don’t notice how meandering evolution is — an animal might become slightly larger one century, slightly smaller the next. And the reason neither process amounts to ‘evolving backward’ is because neither process is ‘evolving forward’ either — all hereditary change is evolution, regardless of ‘direction’.

Second, although we enjoy thinking of ourselves as the ‘goal’ of evolution, we don’t think about the hundreds of millions of other species that were perfectly happy evolving into organisms radically different from us. Bacteria make up the majority of life’s diversity; if intelligent bipeds were the aim of all evolution, we would expect them to have evolved thousands of times, not just once.

MYTH 4: We evolved from monkeys.

You may have heard the question asked: ‘If humans descended from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?’ Next time you hear this, feel free to reply: ‘If Australians descended from Europeans, why are there still Europeans?’

Biologists have never claimed that humans evolved from monkeys. Biologists do believe that humans and monkeys are related — but as cousins, not parent and child.

But then, biologists also claim that all life is distantly related. This theory, common descent, is the real shocker: You’re not only related to monkeys, but to bananas as well! This is based on the fact that all life shares astonishing molecular and anatomical simliarities, and these commonalities seem to ‘cluster’ around otherwise-similar species, like lions and tigers. Just as DNA tests make it possible to determine how closely related two human beings are, so too, by the same principle, do they allow us to test how closely related two different species are.

In the case of humans, the molecular evidence suggests, not that we descended from monkeys, but that we shared a common ancestor with them tens of millions of years ago. This ancestor was neither a modern monkey nor a human, but a now-extinct primate. Humans and monkeys have both evolved a great deal since that time. We’ve just evolved in very different ways.

It should also be noted that we are much closer to the other apes than to true ‘monkeys’ (which have longer tails). Humans are classified in the great ape family, the hominids. This makes our closest living cousins the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, and gibbon — but we didn’t evolve from them, any more than they evolved from us.

MYTH 5: Evolution is random.

It’s sometimes suggested that evolution is too ‘blind’ and ‘random’ to result in complicated structures. But natural selection is only ‘random’ in the sense that physical processes like gravity are ‘random’. Although the genetic differences between organisms derive in part from random mutations, natural selection nonrandomly ‘filters’ those differences based on how well they help the organism survive and reproduce in its environment. The overall process of evolution, therefore, isn’t simply random: Species change in particular ways for particular reasons, such as because of a new predator in the region, or for that matter because of the absence of a predator.

A related myth is the notion that evolutionary theory claims ‘life arose by chance’. This is not an aspect of the theory of evolution, which only describes how life changes after it has already originated. Instead, this is relevant to the study of abiogenesis, the origin of life.

MYTH 6: We still haven’t found a ‘missing link’.

It’s not always clear what this fabled ‘missing link’ is supposed to be, as thousands of fossils of early humans and hominids have been discovered. The problem is that every time a new fossil is found that fills a ‘gap’ in the evolutionary record, it just creates two new gaps — one right before the fossil species, and one right after.

Transitional fossils linking major groups of organisms are also abundant in the record. One of the most famous dates back to Darwin’s day: Archaeopteryx, a proto-bird with feathers, teeth, and clawed fingers. More recent examples include Tiktaalik, a fish with primitive limbs (including wrists) and a neck, predating the amphibians.

More to the point, the central lesson evolution has to teach us is that every organism is a ‘link’ — all life is connected, and every organism that has offspring is equally ‘transitional’, because life is constantly changing. The change is gradual, certainly, and seems minute on a human time scale — but one of the profoundest lessons science has to offer is that drops of water, given time, can hollow a stone.

For more information, see Talk.Origins.